On September 26th, 2023, the British Columbia Supreme Court released a landmark ruling in a case brought by the Ehattesaht First Nation, and a parallel case brought by Gitxaala First Nation, challenging the provincial regime that allows for granting mineral tenures without any prior consultation with First Nations regarding their section 35(1) Aboriginal rights and title. The Court agreed with Ehattesaht that the mineral tenure regime is contrary to the constitutional obligation of the Crown to consult with First Nations prior to conduct that can affect their rights and title. The Court held that the problem with the mineral tenure regime is “systemic” and that the regime must be fixed for the entire province. The Provincial government has 18 months to work with First Nations to develop a regime that is consistent with the duty to consult and that furthers reconciliation.

This case was brought by a team of Ratcliff lawyers including Lisa Glowacki and Grace Hermansen.

The current mineral tenure system is based on the “free miner” system dating back to the Gold Rush. It allows individuals to claim exclusive rights to minerals by registering title online with the push of a button. There is no requirement for consultation with First Nations and no account taken of their interests or rights in the territories.

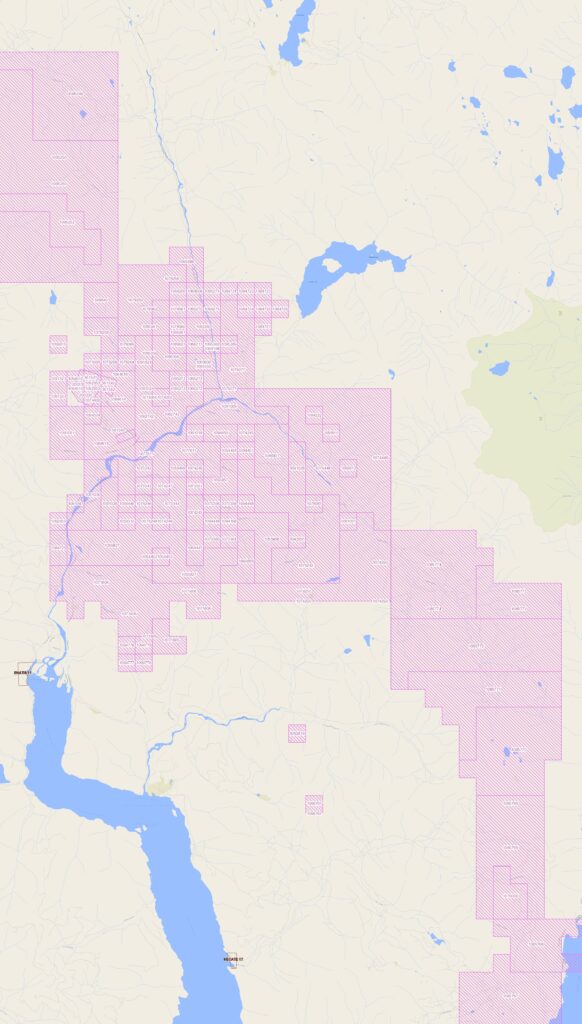

The Court declaration that the mineral tenure regime violates the duty to consult is very important for Ehattesaht, who face significant mineral exploration and mining activity in their Ha-Hahoulthee and who seek meaningful co-management and decision-making that reflects and protects their rights and interests. There are more than 100 active mineral claims in Ehattesaht’s Ha-Hahoulthee- all of which were issued without consideration of Ehattesaht’s rights and title.

Justice Ross of the BCSC was clear that the grant of mineral tenures conflicts with Ehattesaht’s Aboriginal title interests, which include minerals, and Ehattesaht’s cultural and spiritual practices, including the protection of crystals in their Ha-Hahoulthee. The findings of the Court are important and worth setting out here:

- [396] In summary, I [Justice Ross] am not persuaded by any of the province’s submissions regarding the granting of mineral rights and its physical impact on the petitioners. I find that the grant of a mineral claim:

- a) confers the right to remove a prescribed amount of minerals from the claim area. The loss of minerals reduces the value of the territory and, thus, adversely affected Aboriginal rights and title;

- b) transfers some element of ownership of minerals to the recorded holder. The petitioners assert rights to those minerals in this case and, therefore, consultation is required prior to transferring those rights to a third party;

- c) confers the exclusive right to explore for minerals with the area. That right provides a financial benefit, the right to raise capital through investment. The First Nation is deprived of that opportunity; and

- d) affords the recorded holder the right to disturb the land. While the parties do not agree on the breadth of that right, in my opinion, viewed from the Indigenous perspective, the allowable disturbance is greater than “nil or negligible”.

As a result of the Court’s decision, mineral tenures can no longer be granted without taking these Aboriginal interests into account.

“This is a major victory for our people” said Ehattesaht Chief Simon John. “For more than a century mining has damaged our territory and our resources have been taken including our sacred crystals, gold, and much more. This decision, which recognizes our rights to our land, is an important step toward self-determination for our nation.”

Chief John said “Decisions on mining can no longer be taken in isolation by the Province. Tenures are the first stage in mining- these initial grants of rights cannot be made without our involvement.” He confirmed: “We look forward to working with the Province to develop a new way to approach mineral tenuring and to create shared decision-making frameworks for resource development in Ehattesaht territory. This is the necessary path for the health of our territory, for our people and our rights, as well as for the government and industry – it is the way that everyone can move forward with confidence, respect, and certainty.”

The result of the Court’s decision on the duty to consult arising from the honour of the Crown and section 35(1) of the Constitution is very powerful. Unfortunately, the Court decision is regrettable in the treatment of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). The Court heard arguments from Gitxaala, Ehattesaht, the First Nations Leadership Council, the BC Human Rights Commission and other intervenors about the significance of both the provincial DRIPA legislation as well as UNDRIP to the application of the laws of British Columbia.

The Court was asked to make a finding that the mineral tenure regime, in denying any duty to consult, was inconsistent with the indigenous rights in UNDRIP, including to free, prior and informed consent to resource development. The Court refused to make the declaration and instead accepted the arguments put forward by the Province that: “[DRIPA’s] provisions do not reflect a legislative intention to give immediate legal force and effect to [UNDRIP’s] provisions or to create a justiciable legal standard for the alignment of British Columbia’s laws with [UNDRIP].” DRIPA evinced a political commitment to work with First Nations, not enforceable legal standards (or rights). The Court accepted the Province’s position.

Whether UNDRIP and DRIPA can have more legal force will need to wait until future decisions of the court. In the meantime, Ehattesaht expects that the Province will uphold its political commitment to implement and bring the laws of the Province in line with UNDRIP, and, to finalize and put in place co-management and decision-making agreements with First Nations regarding resources in their territory. The decision of the Court confirms that section 35(1) of the Constitution remains a powerful protection for First Nations’ rights and interests and a source of enforceable obligations of the Crown.

Ratcliff is honoured to have represented Ehattesaht in the court claim and looks forward to a regime change that upholds First Nations’ rights and the Crown’s obligations. Land-management that recognizes First Nations’ rights and governance is a fundamental and necessary step in the path toward reconciliation.

The court decision can be found at: Gitxaala v British Columbia (Chief Gold Commissioner), 2023 BCSC 1680

Background on Mining in Ehattesaht Ha-Hahoulthee

Mining arrived in Ehattesaht Ha-Hahoulthee near the turn of the previous century with the discovery of small gold deposits in the Zeballos River Valley and the development of very tiny underground shafts drilled by hand where mules packed ore to the beach. Toward the 1950’s the industry expanded to include an expansive underground iron ore mine and deep seaport on tailings to larger underground gold mines with milling on site. Much of this activity stopped in the late 1960’s when the Mining Act changed to attach ongoing environmental liability to operating mining companies. As a result, the Ehattesaht Ha-Hahoulthee has a number of long abandoned workings which include tailing ponds, tailing mounds, and exposed mine shafts that produce run off water. There are current applications for mining projects in the Ha-Hahoulthee which have yet to be approved and Ehattesaht and BC are working on building a consent-based decision making model for ongoing and future mining projects. Mineral tenures are an integral stage in mine development, and the court-recognized duty to consult at this early stage is an important correction to how mining has occurred so far.